Benchmarks measure outcomes, not behavior. By letting AI models play chess in repeatable tournaments, we can observe how they handle risk, repetition, and long-term objectives, revealing patterns that static evals hide.

Evaluating AI models is hard. Not because we lack metrics, but because what we care about often doesn’t fit neatly into a single number. We want to understand how models behave over time, how they respond to complex situations, how they compare to one another, and where they fail in surprising ways.

So instead of another benchmark chart, let’s do something more fun. Let’s play chess.

Chess turns out to be a great playground for thinking about model evaluation. It is structured, adversarial, and stateful, with clear outcomes: win, lose, or draw. Better yet, it lets us simulate model behavior repeatedly and compare models head-to-head.

Before we go further, it’s worth clarifying what this evaluation is and isn’t. This isn’t about measuring chess skill or producing a leaderboard. It’s about observing behavior over time: how models handle repeated states, how they trade off risk versus safety, and which failure modes only appear after many interactions. Chess provides a compact, stateful environment where these dynamics are easy to surface and compare.

A Repeatable, Programmatic Evaluation Setup

We use the Python chess library to simulate games programmatically. Each “player” is simply a function that, given a board position and a list of legal moves, chooses its next move.

Dagster orchestrates everything: tournaments, players, configurations, results, and artifacts. A tournament job looks something like this:

ops:

tournament_start:

config:

num_games: 100

player_1: megan

player_2: thomasEach tournament:

- Runs a configurable number of games

- Alternates colors so each player plays White an equal number of times. White moves first and has a slight advantage.

- Enforces a maximum number of moves to avoid infinite games

- Records outcomes and final board states as Dagster artifacts

With that in place, we can start experimenting.

Baseline: No Objective, No Strategy

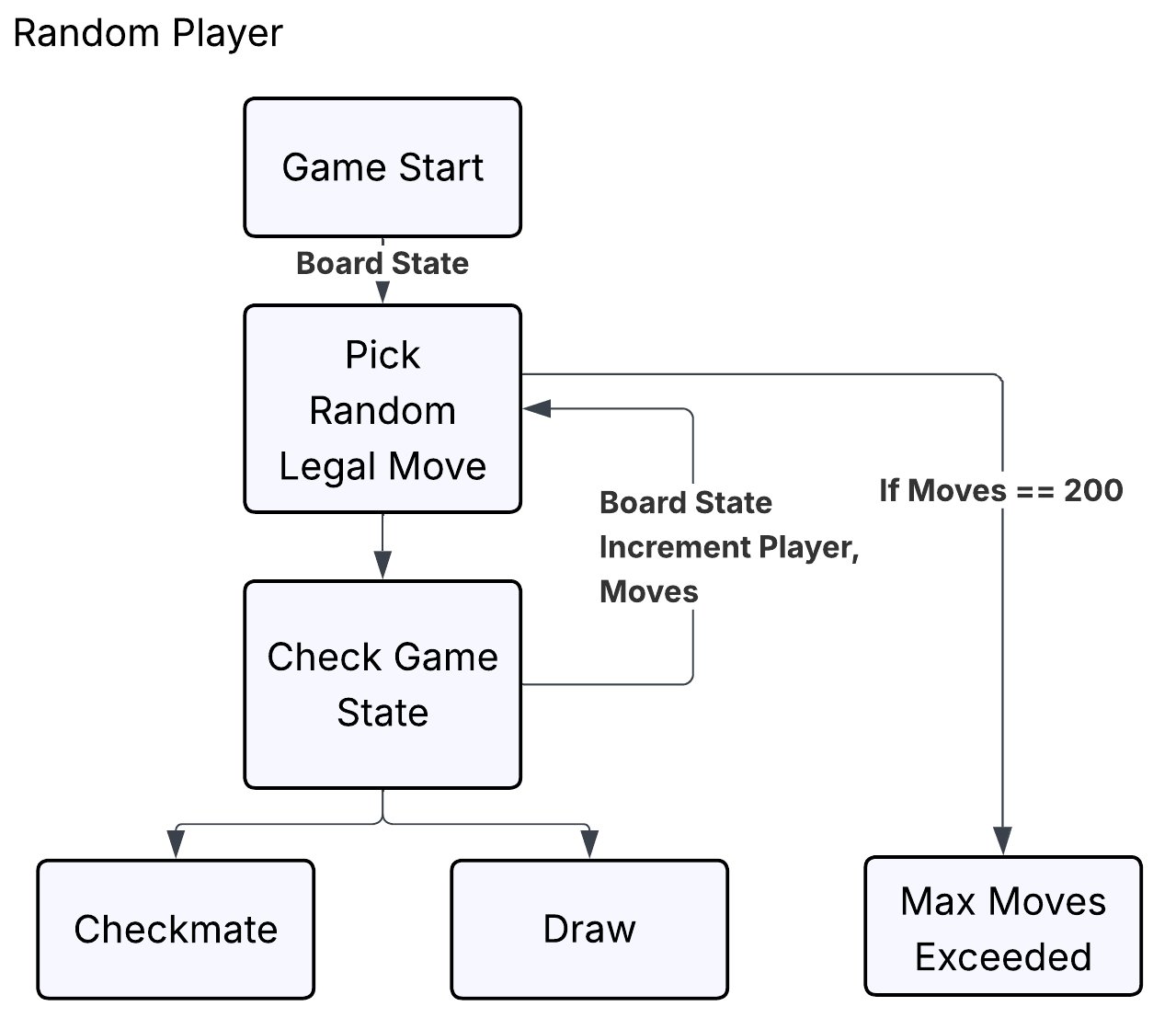

“Megan” and “Thomas” are random agents using the Python chess library and Python’s random module. On each turn, they select a move at random from the list of legal moves and hope for the best. After each move, we use the chess library to check the state of the game and determine whether either player has won.

Using Dagster, we pit Megan and Thomas against each other in a 100-game tournament. One thing becomes clear almost immediately: neither player is particularly good at chess. Of the 100 games played, 87 ended in draws due to the maximum limit of 200 moves.

In the remaining 13 games, there was a decisive result. Thomas managed to defeat Megan by a narrow margin, winning 7 games to Megan’s 6.

We can also store the final board state of each game as a Dagster artifact. Below is the board position from one of Thomas’s rare victories.

The takeaway here is not that randomness is good at chess. It is that we now have a baseline. If a model cannot outperform random play, that tells us something immediately.

Baseline: Explicit Objectives and Long-Horizon Optimization

Now we can jump to the other extreme. Stockfish is an AI chess engine. Unlike our first set of players randomly flinging pieces at each other, Stockfish is very good at chess. Elo, the numerical rating system used in chess, estimates Stockfish at around 3600. For context, the highest Elo rating ever achieved by a human is 2882, held by Magnus Carlsen.

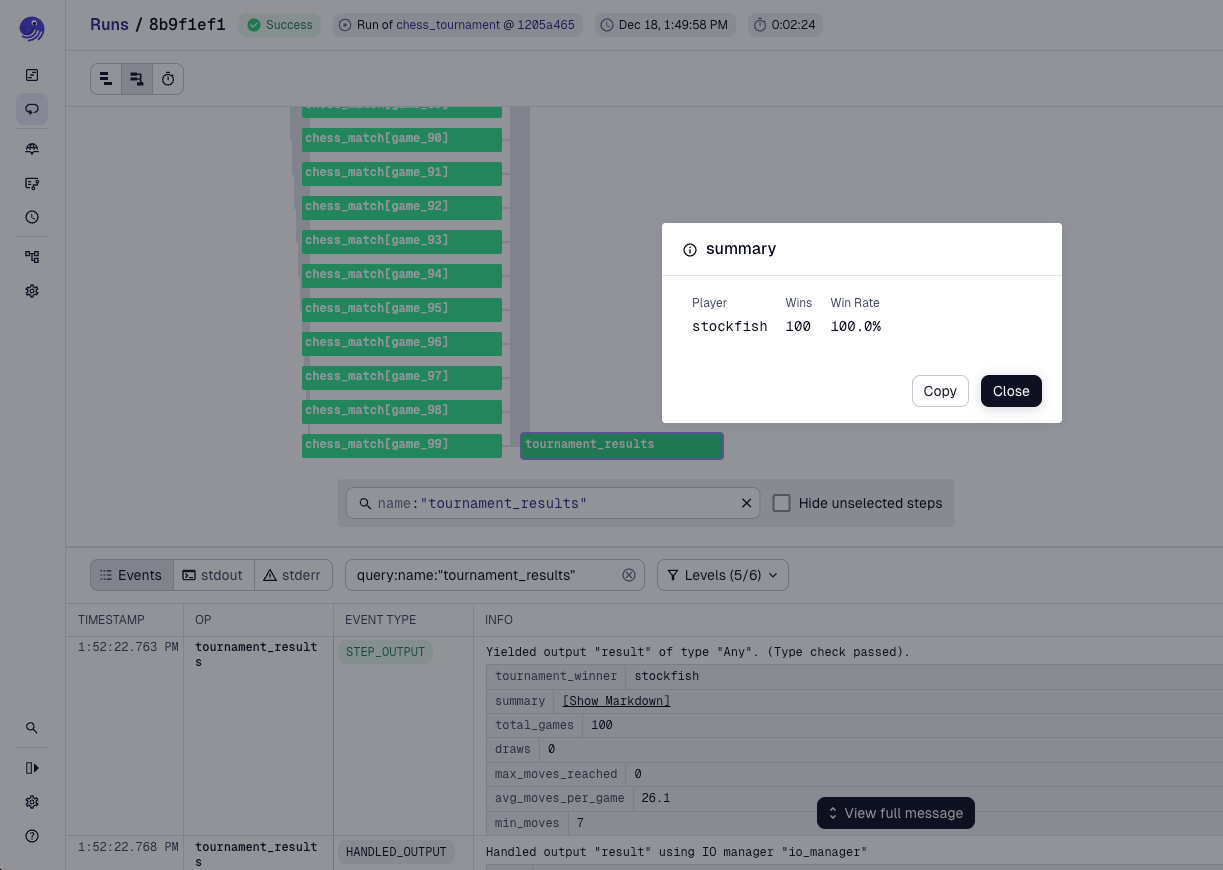

Thomas now has the honor of playing against Stockfish.

ops:

tournament_start:

config:

num_games: 100

player_1: stockfish

player_2: thomasAs expected, Stockfish defeats Thomas in every game. It also wins quickly, with an average game length of just 26 moves, compared to the excruciating 189 moves it took Thomas and Megan to finish a game on average.

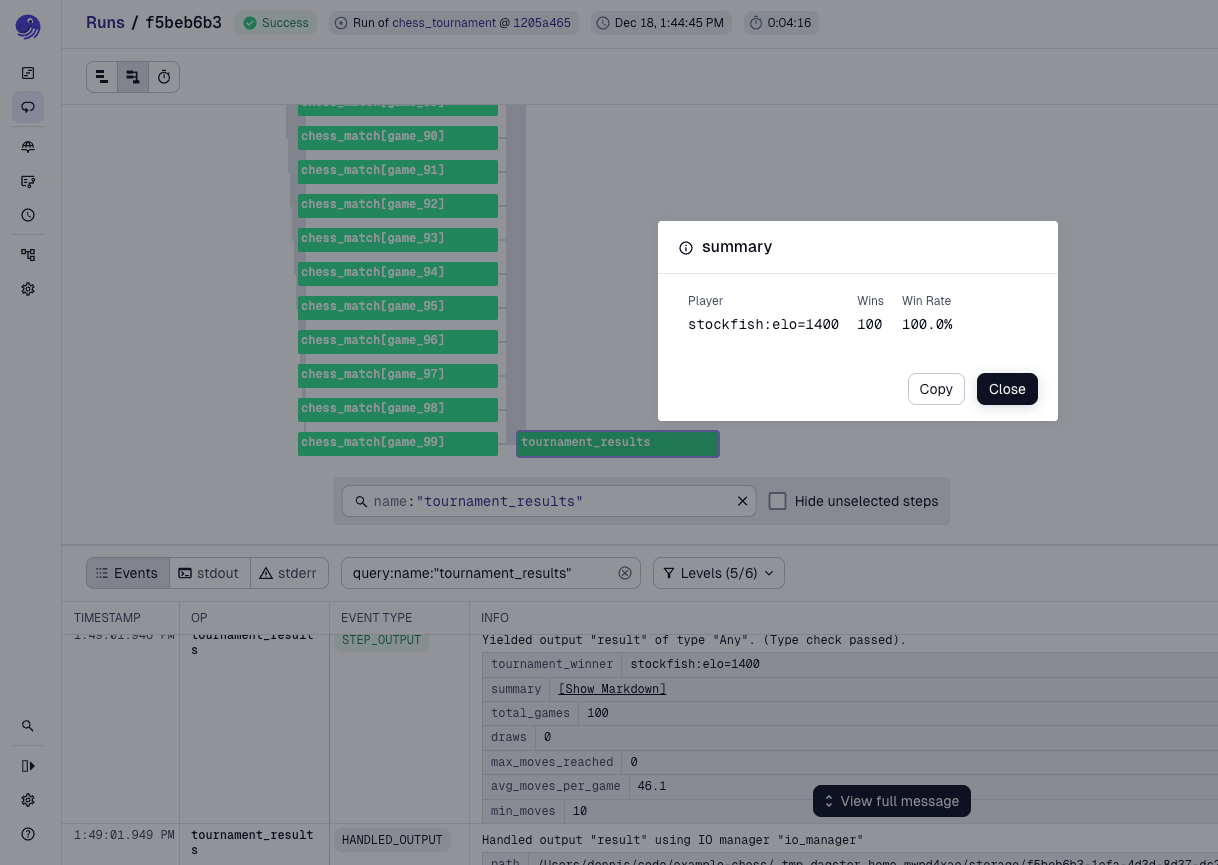

This result is not surprising. Human players cannot reasonably expect to beat Stockfish. To make things more interesting, we can adjust Stockfish to play at a lower level. In the next tournament, Stockfish behaves like a player with an Elo rating of 1400.

ops:

tournament_start:

config:

num_games: 100

player_1: stockfish:elo=1400

player_2: thomasA rating of 1400 represents a solid intermediate player. This is still more than enough to beat Thomas in every game, although Stockfish now needs a few more moves to do so, averaging 46 moves per game.

Now that we understand the two extremes of our simulated chess environment, it is time for the interesting part.

Evaluating General-Purpose Models Under Identical Constraints

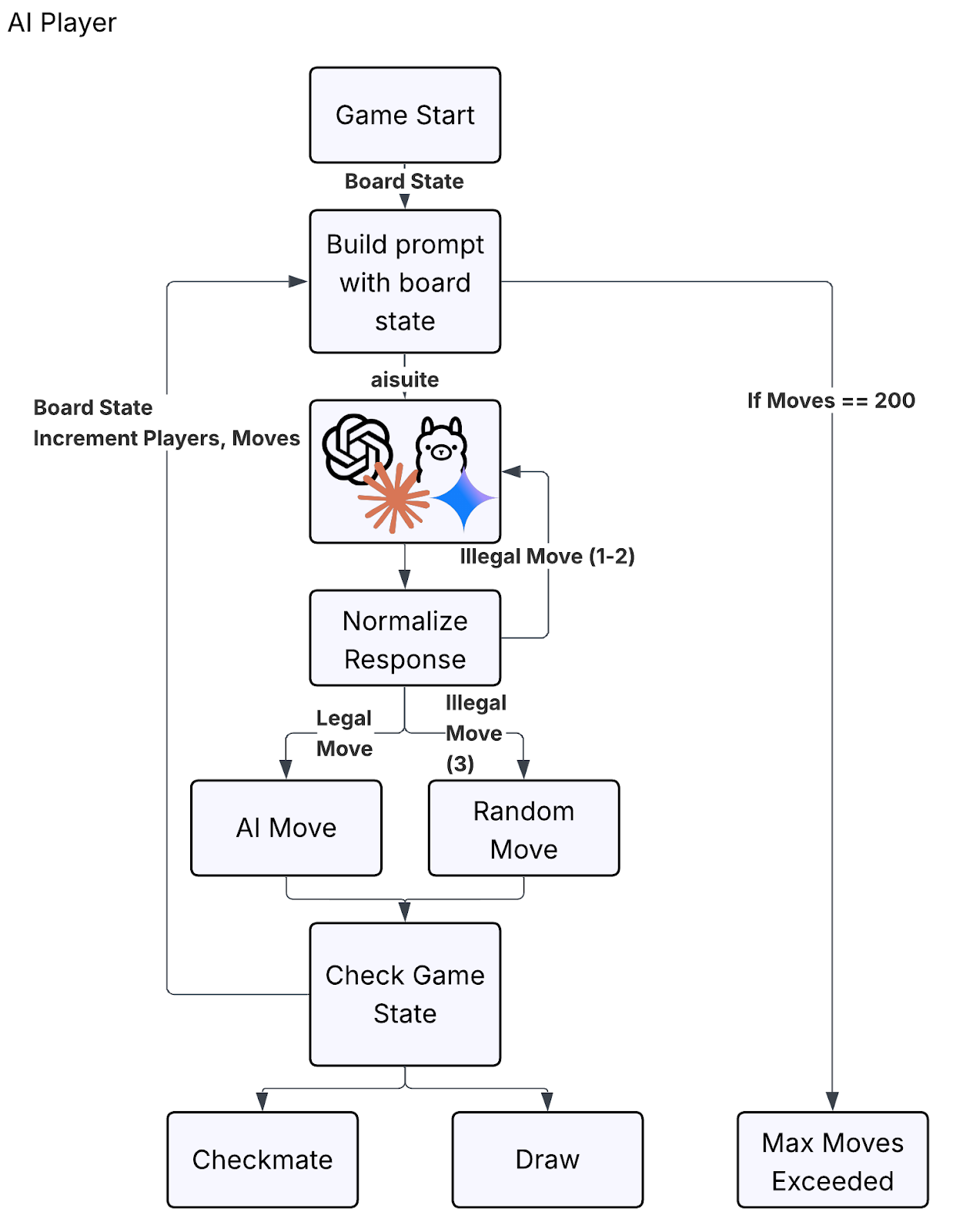

We are now ready to introduce general-purpose AI models into our tournament. The goal is to let any model play chess without having to worry about the implementation details of different APIs.

This is where aisuite comes in. aisuite provides a consistent interface across models from OpenAI, Anthropic, Gemini, and several others. With it, we can supply the same prompt to every model and evaluate them under identical conditions.

We start by defining a system prompt that instructs the model to play chess with the intent to win. The prompt emphasizes common chess heuristics such as controlling the center, developing pieces, avoiding blunders, and looking for checkmates.

CHESS_SYSTEM_PROMPT = """You are a chess grandmaster playing to WIN. Choose the BEST move to defeat your opponent.

Strategy priorities:

1. CHECKMATE: Look for moves that checkmate or set up checkmate threats

2. WIN MATERIAL: Capture undefended pieces, look for forks/pins/skewers

3. ATTACK THE KING: Target the enemy king, especially if uncastled

4. CONTROL CENTER: Occupy and control e4, d4, e5, d5

5. DEVELOP PIECES: Get knights and bishops out early, castle for king safety

6. AVOID BLUNDERS: Don't hang pieces or walk into tactics

You will receive the board, your color, and legal moves in UCI notation.

Think about which move gives you the best winning chances.

Respond with ONLY the best move in UCI notation (e.g., e2e4, Nf3, e7e8q).

No explanation - just the single best move."""This prompt is intentionally simple. It encodes high-level chess heuristics, but it does not give the model a true evaluation function, search capability, or explicit penalties for repetition. That’s by design. In practice, general-purpose models are often evaluated through instructions rather than task-specific training. The goal here isn’t to build a strong chess engine, but to see how different models behave when given the same objective under identical constraints.

Next, we wrap this logic in a custom Dagster resource that handles communication with aisuite. This resource is responsible for formatting prompts, handling model-specific quirks, and returning a single legal move in UCI notation.

class AISuiteResource(dg.ConfigurableResource):

temperature: float = 0.75

_client: ai.Client = PrivateAttr(default_factory=ai.Client)

def chat(self, model: str, messages: list[dict]) -> str:

kwargs = {"model": model, "messages": messages, "temperature": self.temperature}

response = self._client.chat.completions.create(**kwargs)

return response.choices[0].message.content

def get_chess_move(

self,

model: str,

board_str: str,

is_white: bool,

legal_moves: list[str],

max_moves_shown: int = 30,

) -> str:

color = "W" if is_white else "B"

moves_to_show = legal_moves[:max_moves_shown]

if len(legal_moves) > max_moves_shown:

moves_str = f"{', '.join(moves_to_show)} (+{len(legal_moves) - max_moves_shown} more)"

else:

moves_str = ", ".join(moves_to_show)

user_content = f"""{board_str}

{color} to move. Legal: {moves_str}"""

# o1/o3 models don't support system prompts - include instructions in user message

if model in NO_SYSTEM_PROMPT_MODELS:

messages = [

{

"role": "user",

"content": f"{CHESS_SYSTEM_PROMPT}\n\n{user_content}",

},

]

# o1 models also don't support temperature

move = self.chat(model=model, messages=messages, temperature=None).strip()

else:

messages = [

{"role": "system", "content": CHESS_SYSTEM_PROMPT},

{"role": "user", "content": user_content},

]

move = self.chat(model=model, messages=messages, temperature=0.3).strip()

return move

With this in place, calling a model to get its next chess move becomes straightforward. We pass in the current board state, whose turn it is, and the list of legal moves.

It is generally unclear what specific chess data each LLM is trained on. Most models contain information about the rules of chess, common notation, annotated examples, and strategic concepts from instructional material, but they are not necessarily trained on a large number of structured chess games.

ai_resource.get_chess_move(

model="openai:gpt-4o",

board_str="""r n b q k b n r

p p p p . p p p

. . . . . . . .

. . . . p . . .

. . . . P . . .

. . . . . N . .

P P P P . P P P

R N B Q K B . R""",

is_white=False,

legal_moves=[

"a7a6", "a7a5", "b7b6", "b7b5", "c7c6", "c7c5",

"d7d6", "d7d5", "f7f6", "f7f5", "g7g6", "g7g5",

"h7h6", "h7h5", "b8a6", "b8c6", "g8e7", "g8f6", "g8h6",

"f8e7", "f8d6", "f8c5", "f8b4", "f8a3",

"d8e7", "d8f6", "d8g5", "d8h4",

"e8e7"

]

)

In this example, the model evaluates the position and returns what it believes to be the best move, such as g8f6.

General Reasoning vs Domain-Optimized Intelligence

Expecting a little too much, the first experiment pits a general-purpose model against Stockfish.

ops:

tournament_start:

config:

num_games: 10

player_1: stockfish

player_2: openai:gpt-4oThe result clearly illustrates the difference between conversational AI and tactical AI. Stockfish wins every game with ease.

Even after lowering Stockfish’s strength to an Elo rating of 1400, the match remains completely one-sided. In fact, GPT-4o performs about as well as lowly Thomas.

This is not especially surprising. Models like Stockfish are extremely good at chess, but only because they are fine-tuned specifically for that task.

When Neither Side Wants to Lose

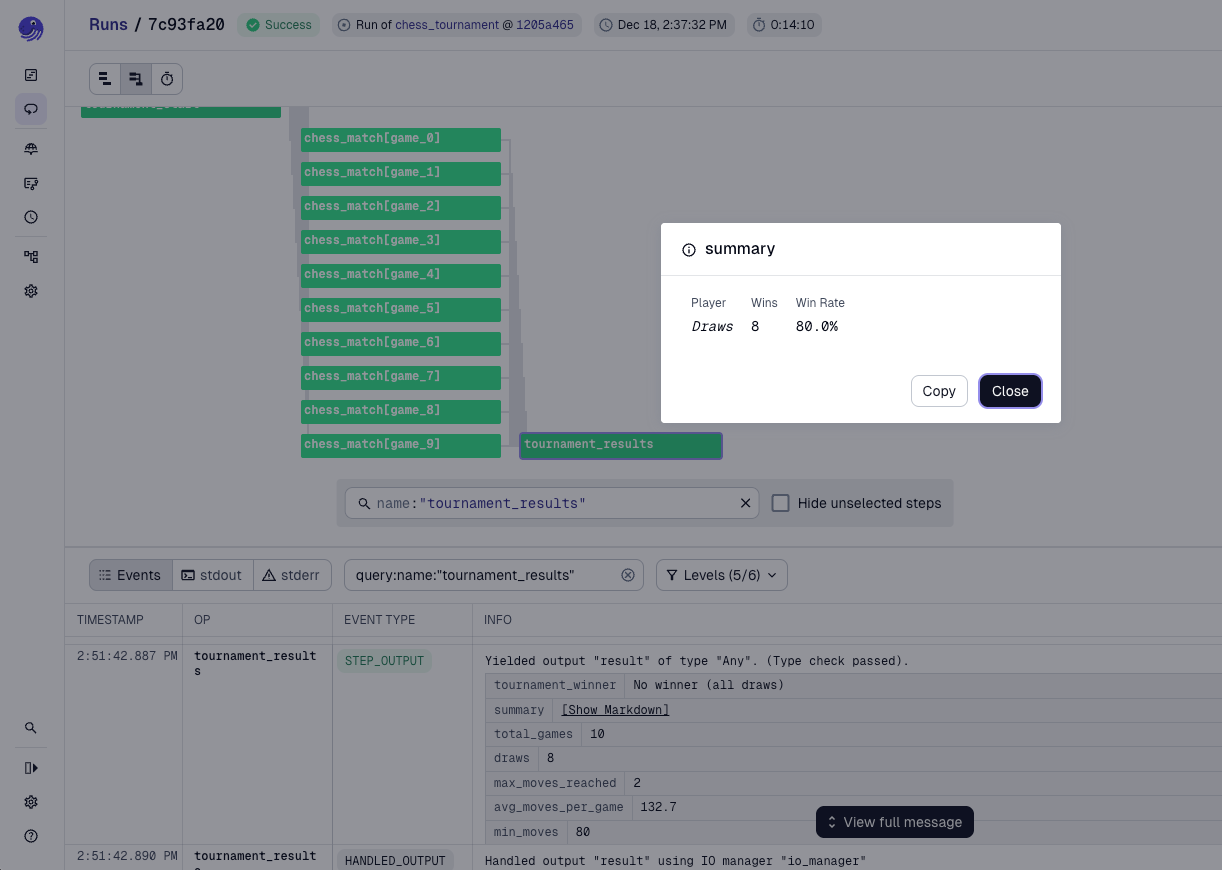

But our goal was never to win at chess. The goal was to evaluate models. So what happens when we play models against each other?

Because we implemented our AISuiteResource, we can swap models freely. As a first comparison, we test one of OpenAI’s more capable models against an older version.

ops:

tournament_start:

config:

num_games: 10

player_1: openai:gpt-4o

player_2: openai:gpt-3.5-turboI expected GPT-4o to outperform its predecessor. Instead, neither model managed to secure a single win.

Unlike the long, drawn-out games between Megan and Thomas, these draws were not primarily caused by hitting the move limit. In eight of the ten games, the match ended due to fivefold repetition.

Fivefold repetition is a chess rule that automatically declares a draw if the exact same position occurs five times, including piece placement, side to move, castling rights, and en passant possibilities.

In other words, both models were playing better than random, but not aggressively enough to gain an advantage over one another.

Again part of this may be due to the prompt. More elaborate prompts (e.g. penalizing repetition or rewarding material imbalance) could dramatically change behavior, but at the cost of baking assumptions into the eval.

Cross-Vendor Models, Identical Outcomes

For one final experiment, we pit models from different companies against each other.

ops:

tournament_start:

config:

num_games: 10

player_1: openai:gpt-4o

player_2: anthropic:claude-3-haiku-20240307

Because Dagster handles orchestration and aisuite abstracts away model differences, this comparison requires no changes to the evaluation logic. The models can be swapped in and out freely, making it easy to extend these experiments as new models become available or as vendors release updated versions.

Going into the experiment, I expected the Anthropic model to perform slightly better. Claude models are often strong on structured reasoning and logical consistency, which I assumed would translate into better chess play. However, every single game ended in a fivefold repetition draw.

This behavior is not surprising when you consider how general-purpose language models are trained. They are optimized to avoid errors, contradictions, and irreversible bad outcomes. In chess, that bias often manifests as repetition. Repeating known safe positions is a reliable way to avoid losing, especially when the model lacks a strong internal evaluation function for long-term advantage.

The results show some of the gap between general reasoning ability and domain-specific competence. Even very capable language models do not automatically become strong chess players just because chess is a logical game. Without fine-tuning or reinforcement learning on chess-specific objectives, the models lack the incentive structure needed to prefer winning over merely not losing.

Fine-tuned chess engines (Stockfish) are explicitly trained to evaluate positions, take calculated risks, and avoid stagnation. They are rewarded for progress and penalized for repetition. General LLMs, by contrast, are rewarded for plausibility and safety, which makes repetition a locally optimal strategy.

Why Safety-Optimized Models Prefer Stagnation

Chess was never the goal.

What matters is what it gives us: a structured, stateful environment where model behavior becomes visible over time. By running repeatable tournaments, we can see not just whether a model succeeds, but how it behaves when faced with the same situations again and again.

Dagster makes these simulations observable and repeatable, while aisuite lets us compare models under identical conditions with minimal friction. Together, they make it easy to move beyond static benchmarks and toward evaluations that reflect real behavior.

Benchmarks still matter, but they only tell part of the story. When you want to understand how models actually behave, sometimes the best approach is to let them play a game.