When agents write tests, intent matters as much as correctness. By defining clear testing levels, preferred patterns, and explicit anti-patterns, we give agents the structure they need to produce fast, reliable Pytest suites that scale with automation.

In a previous post, we discussed some of the stylistic choices we use internally to ensure that Python code generated by our agents remains “dignified.” These rules, covering style, structure, and idiomatic Python, help us maintain a consistently high-quality codebase even when much of the code is machine-assisted.

However, when we write code with assistance, our agents must also be held to the same standard for tests. In practice, this means being explicit about how we instruct our agents to design and write tests without introducing subtle errors or long-term maintenance issues.

This requires repository-wide testing strategies that define not just what “good tests” look like, but also when tests should be written, what kinds of tests are appropriate in different situations, and which patterns are disallowed.

In other words, we need to supply the rules and logic that define how tests should be written, not leave those decisions up to inference.

How to Run Agentic Tests

Our testing strategy is designed around skills. Most of the details for these skills can apply to any repo (with some slight changes). But before getting into our actual testing strategy, it is good to discuss how these tests run within our workflows.

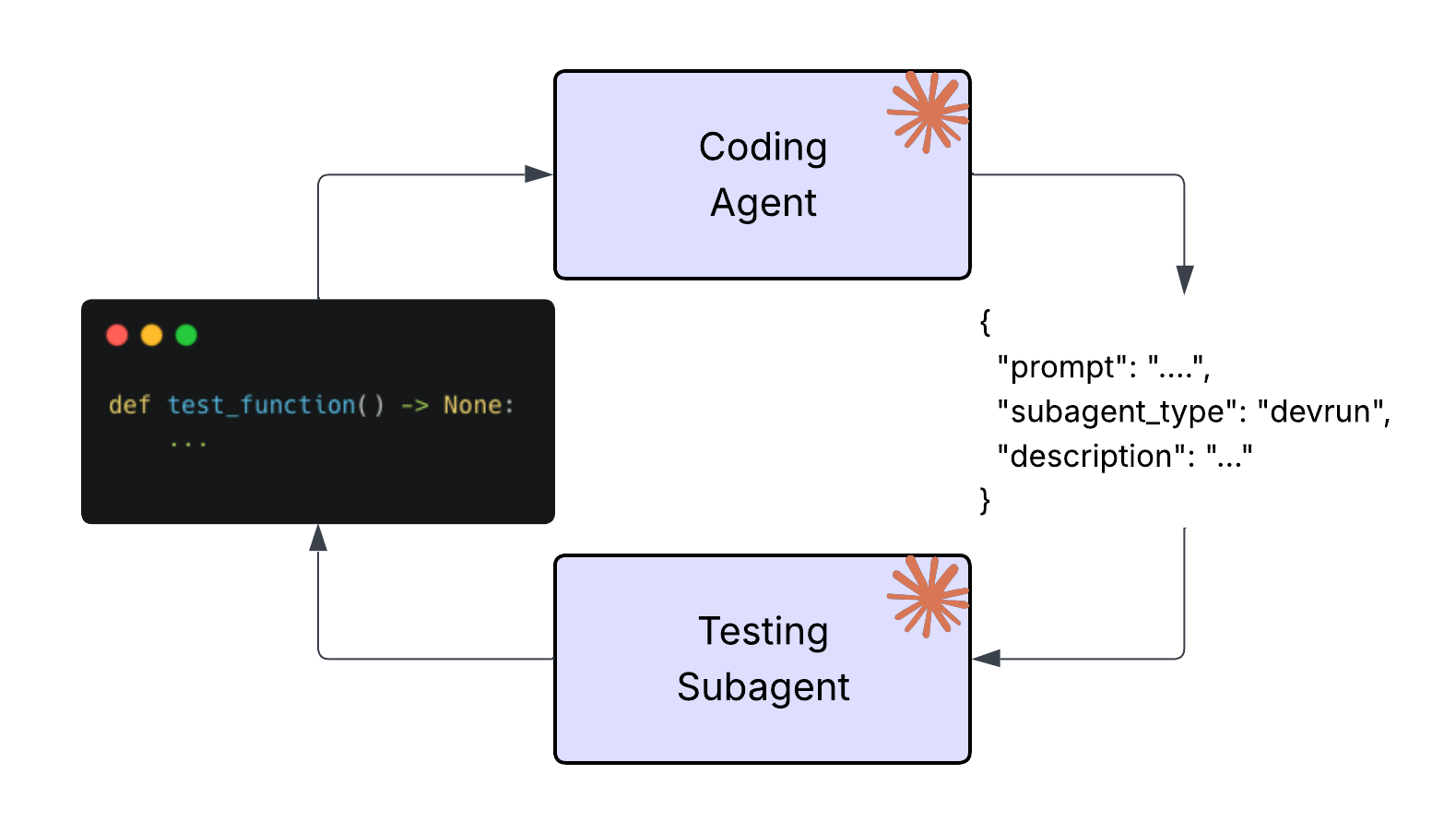

Test-writing agents do not use the same authority or context as agents that produce application code. Test generation runs as sub-agents with a deliberately constrained role within an isolated context window. Constraining test work to a sub-agent prevents the common failure mode where an agent “fixes” a failing test by subtly adjusting the code under test.

Within that sub-agent, each skill represents a narrow task, adding coverage for a specific function, reproducing a reported bug, or refactoring an existing test for clarity. If a request can’t be expressed as a bounded skill, it usually doesn’t belong in an automated test pass.

Finally, we manage context very intentionally. Test sub-agents run with task-specific context and do not accumulate history across runs. This avoids speculative tests, accidental dependency on prior failures, and assertions based on deprecated behavior. Each invocation should be able to stand alone, producing tests that are readable, intentional, and deterministic.

When Agents Write Tests

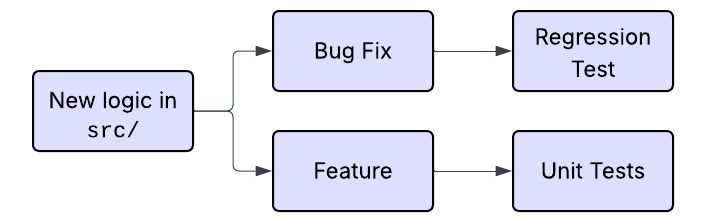

We start with simple workflows. Tests should be written for any new logic introduced under the src directory. We are explicit that agents should only write tests for the code actively being implemented in the current work session.

By narrowing the scope of what an agent is allowed to test, we reduce noise and ensure that tests track real, intentional changes to the codebase.

After limiting the scope of what qualifies as new testable code, we begin to distinguish between code for new feature development vs bug fixes.

Bug fixes, follow a more routine order of operations:

- Write a failing test that reproduces the bug.

- Fix the bug.

- Run the test and confirm that it now passes.

- Leave the test in place as a regression test.

For new features, Test Driven Development is encouraged. We expect appropriate tests to be included alongside the feature, though the specifics of which tests to write, and at what level are slightly more sophisticated.

Choosing the Right Test Level

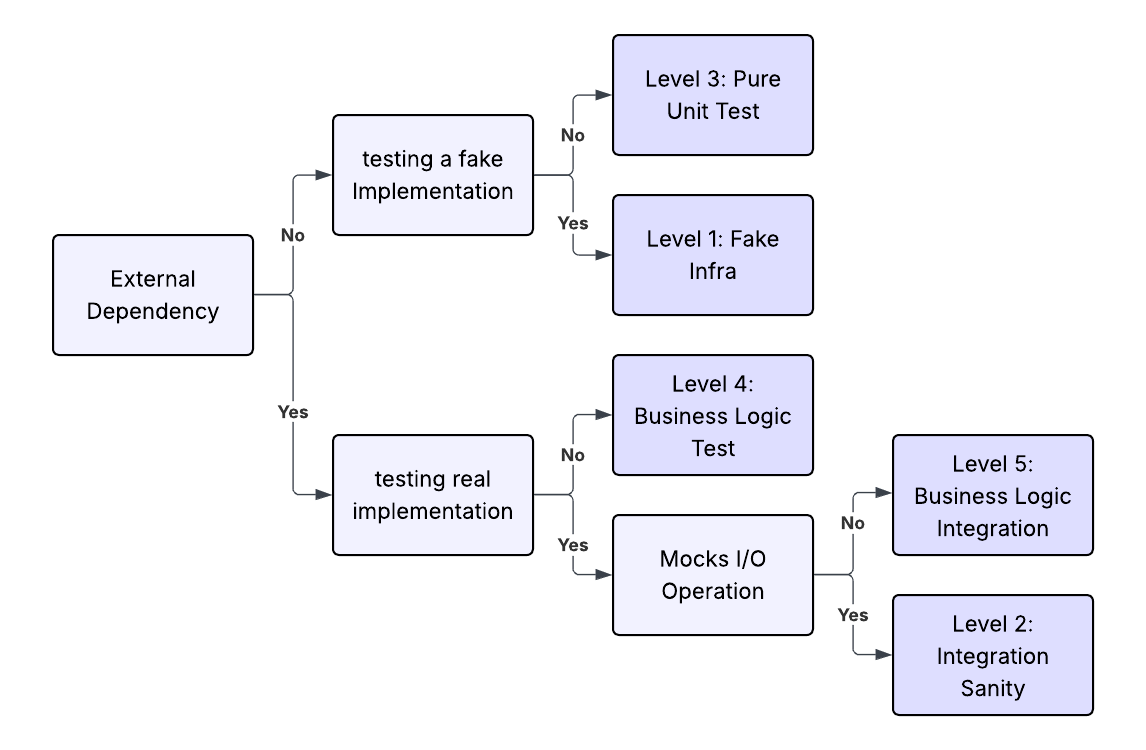

As part of our repository context, we define a number of explicit testing levels. For each level, we describe its purpose and the rough proportion of the overall test suite it should represent. This gives agents a strong prior for where most tests should live.

For example, in one of our codebase, the majority of tests are written against a fake implementation of infrastructure, built specifically for testing. We prefer this approach over heavy use of mocks because they tend to be brittle upon refactoring and can introduce performance and safety issues.

The table for our testing levels reflects this preference by instructing the agent that business logic tests (level 4) should represent the majority of our testing codebase.

This table encodes intent by making the distribution explicit and we signal to the agent where new tests should land.

The routing for each level is handled by logic within the testing-strategy.md skill, were we include include details on when and why certain testing strategies should be chosen:

Layer 4: Business Logic Tests over Fakes (MAJORITY)

Purpose: Test application logic extensively with fast in-memory fakes.

Location: tests/unit/services/, tests/unit/, tests/commands/

When to write: For EVERY feature and bug fix. This is the default testing layer.

Why: Fast, reliable, easy to debug. Tests run in milliseconds, not seconds. This is where most testing happens.This also includes things around which pytest fixtures to use, details on what to test (Feature behavior: Does the feature work as expected?) and paths to example tests to use as reference.

Ensuring that tests are not only written, but written at the correct level of abstraction, in the right place, and using the right supporting infrastructure allows us to build much more quickly with confidence.

Preventing Anti-Patterns

In addition to instructing agents on how to write tests correctly, we must also be explicit about testing anit-patterns. Without these constraints, agents tend to make small local decisions that feel reasonable but can slowly degrade the quality of the test suite over time.

One of the most common failure modes is performance erosion. As tests accumulate, unit tests that were originally lightweight and fast can become bulky and slow, eventually turning into a bottleneck for development and CI.

To counter this, we define both micro-level and macro-level anti-patterns that agents should actively watch for.

Micro-level anti-patterns

At the micro level, we call out specific implementation choices that are inappropriate for unit and business-logic tests. For example:

- Unit tests should avoid invoking

subprocess, which is significantly slower than using the fake infrastructure we include as part of our testing codebase. - Tests should avoid unnecessary filesystem or network interactions when a fake or in-memory alternative exists.

These rules help ensure that individual tests remain cheap to execute and resilient to change.

Macro-level anti-patterns

At the macro level, we define constraints that apply to the test suite as a whole. For example:

- The total runtime of unit tests should not exceed a few seconds.

Performance

Tests over fakes run in milliseconds. A typical test suite of 100+ tests runs in seconds, enabling rapid iteration.This kind of global constraint prevents gradual performance regressions that can be difficult to notice in day-to-day development but are especially damaging at scale.

There are many additional micro-level anti-patterns defined in our repository context, all of which roll up into broader testing objectives defined elsewhere in our repo. By aligning individual rules with higher-level goals, we ensure that our testing strategy remains consistent, non-contradictory, and sustainable as the codebase grows.

Putting the Strategy into Practice

The best way to understand how this strategy works is to look at the tests generated by a real pull request. In this case, the PR adds support for removing installed capabilities from repositories and user settings. Because this is new feature work, new tests are expected and included.

In total, seven tests are added by our subagent, all of which are classified as level 4 business logic tests. This aligns with our expectation that the majority of new tests should validate behavior using fake infrastructure rather than relying on heavy mocking or fully real integrations.

Looking at one of the tests in detail, we can see how these principles show up in practice. Notably, the test does not use @patch decorators or Mock() objects. Instead, it relies on a fake implementation that behaves like the real system while preserving type safety and refactor resilience.

def test_capability_remove_not_installed() -> None:

"""Test that removing a not-installed capability shows warning."""

runner = CliRunner()

with erk_isolated_fs_env(runner) as env:

git_ops = FakeGit(git_common_dirs={env.cwd: env.git_dir})

global_config = GlobalConfig.test(

env.cwd / "fake-erks", use_graphite=False, shell_setup_complete=False

)

erk_installation = FakeErkInstallation(config=global_config)

test_ctx = env.build_context(

git=git_ops,

erk_installation=erk_installation,

global_config=global_config,

)

result = runner.invoke(cli, ["init", "capability", "remove", "learned-docs"], obj=test_ctx)

assert result.exit_code == 0, result.output

assert "Not installed" in result.output

This test validates observable behavior rather than internal implementation details. The important outcomes are that the command exits successfully and that the user receives a clear warning when attempting to remove a capability that is not installed.

assert result.exit_code == 0, result.output

assert "Not installed" in result.outputThe test also respects our defined anti-patterns. It uses CliRunner() rather than spawning a subprocess, avoids hardcoded paths, and relies entirely on the fake infrastructure provided by the test environment. As a result, the test is fast, deterministic, and resilient to refactoring.

Why a Testing Strategy is Still Foundational

Agents remove friction from writing code, but they also remove many of the informal checks humans rely on. Without explicit guidance, tests can become slow, brittle, speculative, or focused on the wrong level of abstraction.

By defining when tests should be written, how workflows differ for features and bug fixes, and which testing levels are preferred, we turn testing into a set of guardrails that scale with automation. Clear anti-patterns further protect the test suite from gradual performance and maintenance regressions.

A well-defined testing strategy makes it possible to move quickly with agents while preserving correctness, confidence, and long-term maintainability. If you want the concrete skill, including our testing guidelines and our "Dignified Python" standards, check out our skills repo.