We set out to explain Dagster assets in the simplest possible way: as living characters that wait, react, and change with their dependencies. By designing a children’s book with warmth, visuals, and motion, we rediscovered what makes assets compelling in the first place.

We think about data platforms a lot. That focus is why Dagster has built a strong following among data professionals designing high-quality systems to support their organizations. Teams at companies like AMD, Fal, and PostHog rely on Dagster to build platforms that push boundaries.

But building great infrastructure is not just about serving the people deepest in the weeds. It’s about helping adjacent engineers, partners, and stakeholders build intuition on how data works. Developing a shared language is especially important for people who don’t work with it every day.

That’s why we care so much about making the fundamental pieces of platform design easy to understand. Even in complex implementations, the core principles behind them are simple enough for a five-year-old to grasp.

Why an Asset Makes a Good Character

The origin of our children’s book is simple. While standing at a conference, our event coordinator said, “I wish we had a children’s book.” It was our first conference featuring our newest book, which naturally attracted our usual audience of seasoned data professionals. At the same time, it made us realize we had never tried anything quite this different.

The next morning, unable to sleep, I started sketching what a Dagster children’s book might look like. Since everything in Dagster revolves around assets, I focused on a single question. What does an asset actually do?

In Dagster, assets are not files or tables in isolation. They come into being, depend on others, and change as the world around them changes. That makes them a natural fit for a story. These behaviors are also sometimes difficult to convey in diagrams, but they are instantly recognizable in characters.

Once we treated the idea of an asset as a living character, the abstraction started to hold its own. When a dependency was not ready, the character had to wait. When new inputs arrive, the character reacts. Without introducing any terminology, the story made the core ideas of Dagster feel obvious.

We were not simplifying assets for a younger audience. We were revealing what they had been all along. Assets map cleanly to how people already reason about the world because they behave like things in the real world.

Designing Something That Feels Alive

Designing a children’s book was refreshing precisely because it broke our usual patterns. We were used to creating tutorials, battle cards, and technical diagrams, formats where clarity comes from structure, labels, and precision. A children’s book demanded something different. It needed warmth, personality, and emotional clarity, not just correctness.

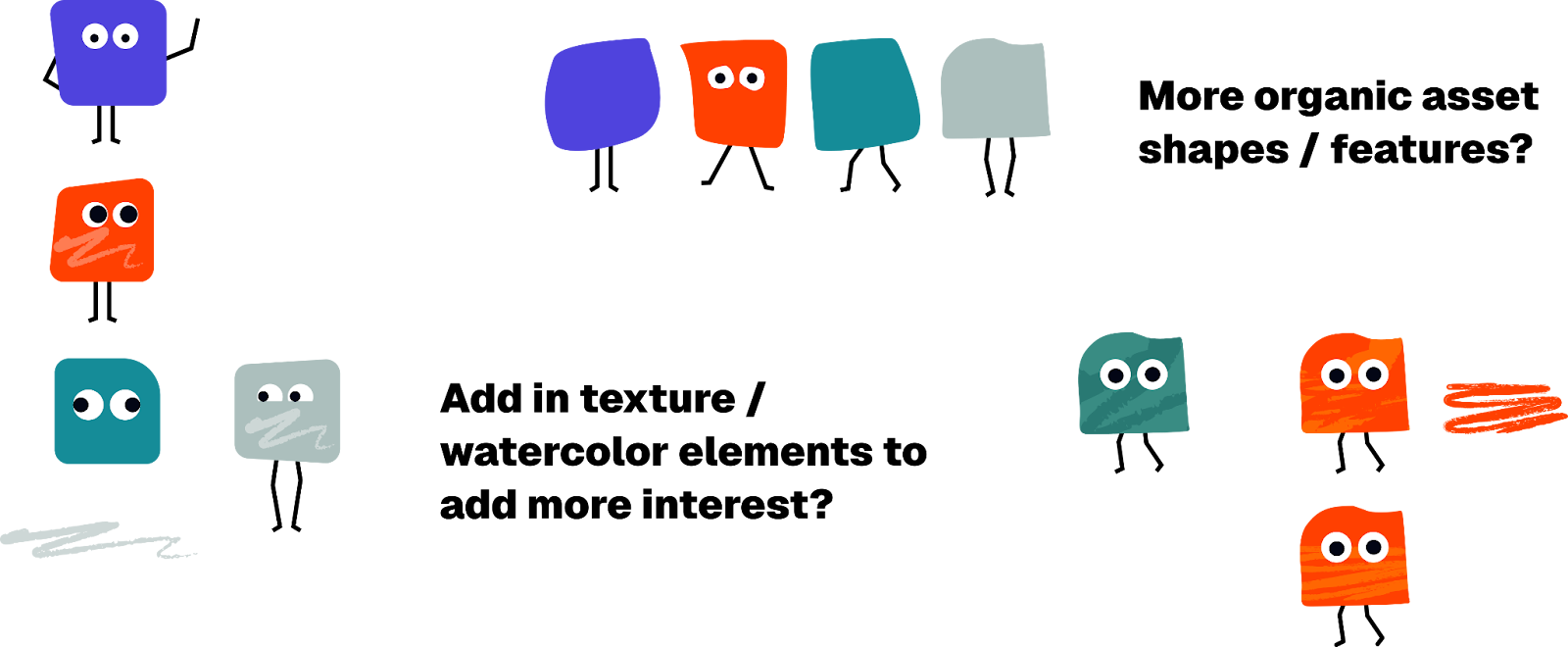

The first design challenge was obvious. What does an asset look like? My original sketches leaned into a playful “poptart” shape that was simple, friendly, and intentionally abstract. The Design team liked the direction but pushed on an important question. Could this character feel less like an object and more like something alive?

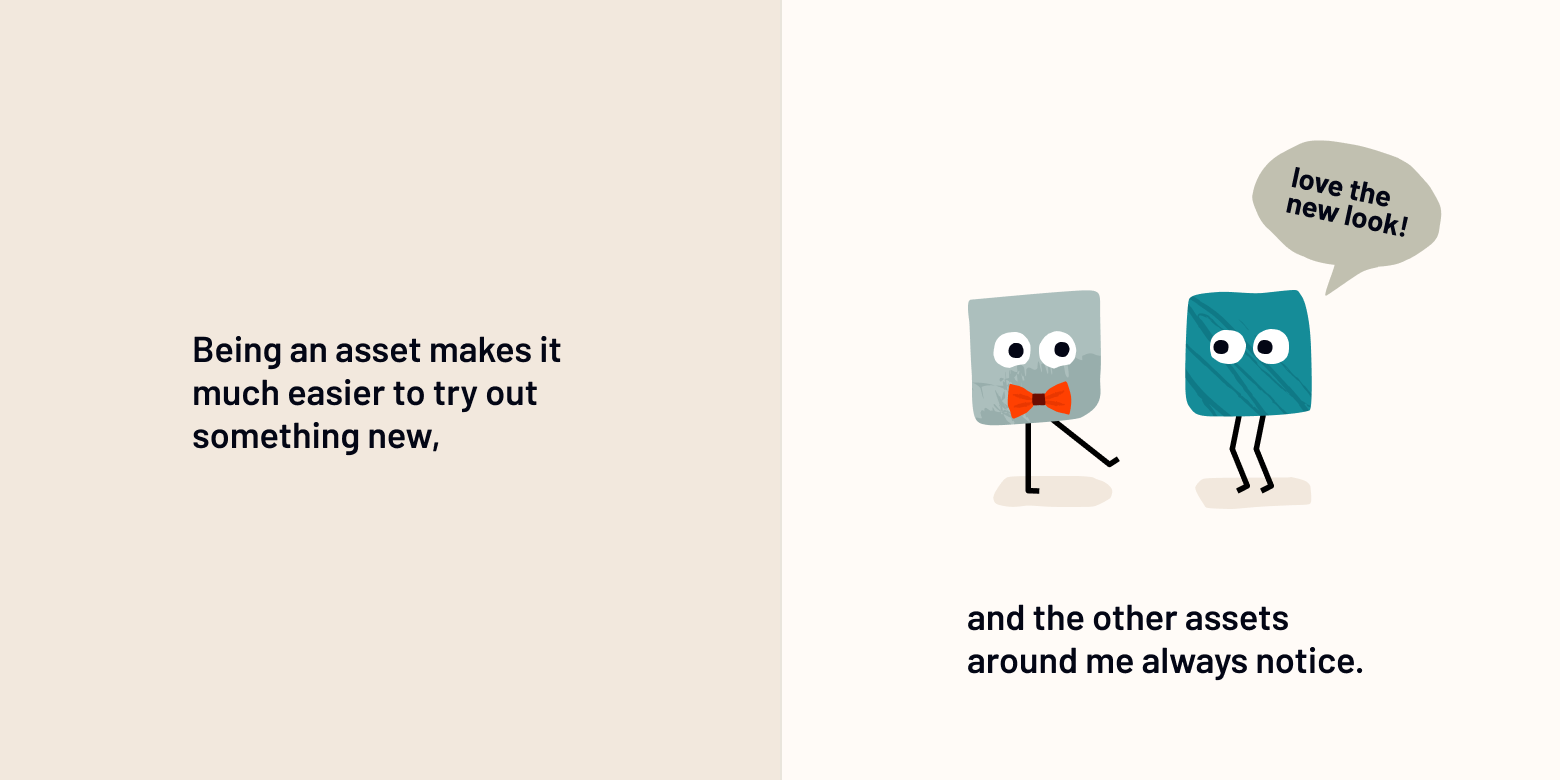

That feedback reshaped the character. Edges softened. Colors became more expressive. Small details gave it a sense of motion and mood. Once the character felt right, attention shifted to the story itself.

The first draft of the book read like a technical explainer in disguise. It carefully walked through ideas we care about deeply, but it asked far too much of its audience. That was a warning sign. If the story needed explaining, the abstraction was not doing its job.

We cut aggressively. Concepts were merged. Explanations were replaced with visual cues. Instead of describing what an asset is, we focused on showing what it experiences. Waiting became a scene. Change became motion. Dependencies became relationships rather than diagrams.

That process forced a hard but useful constraint. If an idea could not be communicated through the character’s actions, it did not belong in the book. The result was a story that felt lighter, more visual, and more intuitive. By the end of the design process, the book no longer felt like a simplified version of Dagster documentation. It felt like its own thing. In making those design choices, we found ourselves rediscovering what made assets compelling in the first place.

Why Motion Matters

We had designed several ebooks in Figma before and built landing pages around them. Those projects typically ended with a static PDF download. We could have taken the same approach with the children’s book, but a static format felt wrong.

The goal of the book was to make assets active. They are created, updated, and shaped by what happens upstream. Animation gave us a way to reflect that dynamism directly. Seeing the character move reinforced the idea that assets change over time rather than existing as fixed objects.

Because the book was already designed in Figma, animation fit naturally into the process. We created small variations of each page, subtle shifts in posture, expression, or environment, and used Smart Animate to stitch them together into a sequence that flowed toward a final frame. The goal was not flashy motion, but continuity. Each transition needed to reinforce the sense that the asset was responding to its world.

These visual cues lowered the barrier for people who had never worked with assets before. Instead of explaining dependencies or updates, the animation showed them. Relationships and change became intuitive, not instructional.

Animating the book also opened the door to narration, completing the illusion. Our event coordinator was enthusiastic enough about the project to lend her voice, giving the story warmth and rhythm that text alone could not provide. That final layer made the book feel fully alive.

What We Learned by Explaining Less

Creating this book reinforced something we already believe deeply. Strong systems are not defined by how complex they are, but by how clearly their core ideas can be understood. Complexity should emerge from simple, well-designed foundations composed at scale.

Working on the book forced us to strip Dagster back to its fundamentals and ask whether those ideas could stand on their own without diagrams, code, or prior context. That exercise proved valuable not just for new audiences, but for us as builders. Explaining something simply is often the best way to test whether it is sound.

We have shared the first physical copies with our team and customers, and we will be bringing them to upcoming conferences for anyone curious to see Dagster through a very different lens. If you’re curious to experience it for yourself, visit the children’s book page to see the animation and hear the story read aloud.